In June 2023, we returned to Scotland to run our ever-popular ‘The Birth of Geology’ tour. Our group of 10 guests travelled from the USA and Canada to experience this wonderful tour around some of the most geologically important places in the United Kingdom, if not the world!

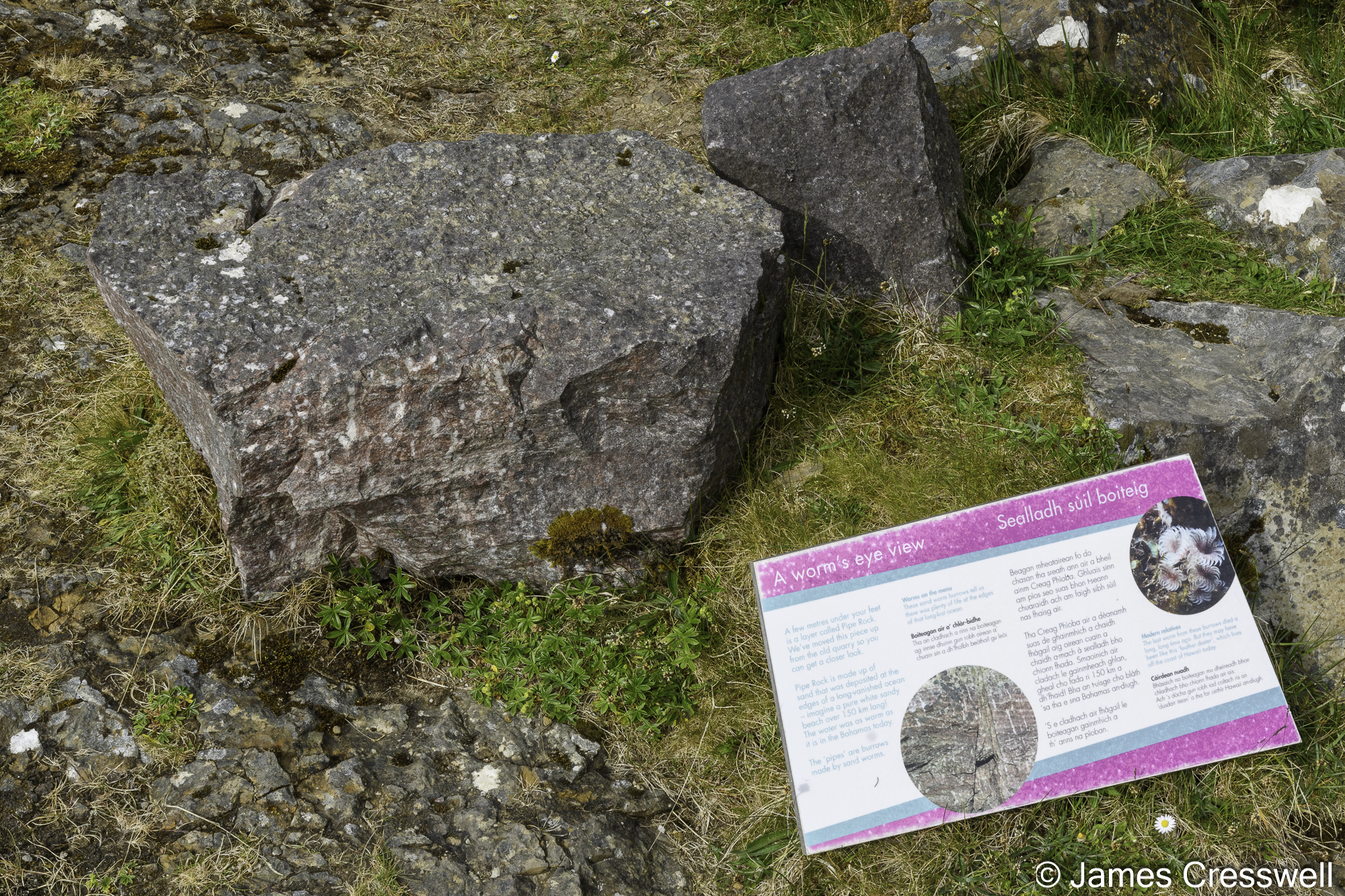

Once again, we started our tour at perhaps the most important site of all – Hutton’s Unconformity at Siccar Point where, in 1788, its discovery laid the foundations for modern geology. From here, we then travelled north, stopping at various sites in the Cairngorms before heading to the Black Isle and then on to the North West Highlands Geopark. Fascinating stops in this area included Knockan Crag and various locations of the Moine Thrust. The tour then moved on to the Isle of Skye, enjoying the awe-inspiring scenery of the Black Cuillin, the Quirang and the dinosaur footprint sites. A boat trip out to Staffa and Lunga included the chance to get up close and personal with the iconic site of Fingal’s Cave. The tour concluded with a spectacular drive south through Glencoe and back to Edinburgh, where we came full circle and completed the tour at Hutton’s Section on Salisbury Crags in Holyrood Park. We were fortunate enough to have outstanding weather for the tour this year, which really emphasised the geological outcrops and the beautiful scenery.

There were so many photos to choose from, but the following 40 photos are our favourite. We hope you enjoy our pictorial record of this year’s tour! You can click on the photos to enlarge them.

Above left: Some of our group at Siccar Point, which has been described as the world’s most important geosite. It was here, in 1788, that James Hutton first realised the enormity of geological time after observing this unconformity.

Above top right: Schiehallion Mountain, where the first attempts to measure the mass of the Earth were made – seen here from the Queen’s View.

Above bottom right: Loch Ness is situated on the Great Glen fault which is a strike slip fault that separates the Northwest Highlands Terrane from the Grampian Terrane. In the Caledonian Orogeny there would have been a lateral movement of hundreds of kilometres on this fault. The loch is also the largest volume of fresh water in Britain, with more water than all the lakes of England and Wales combined.

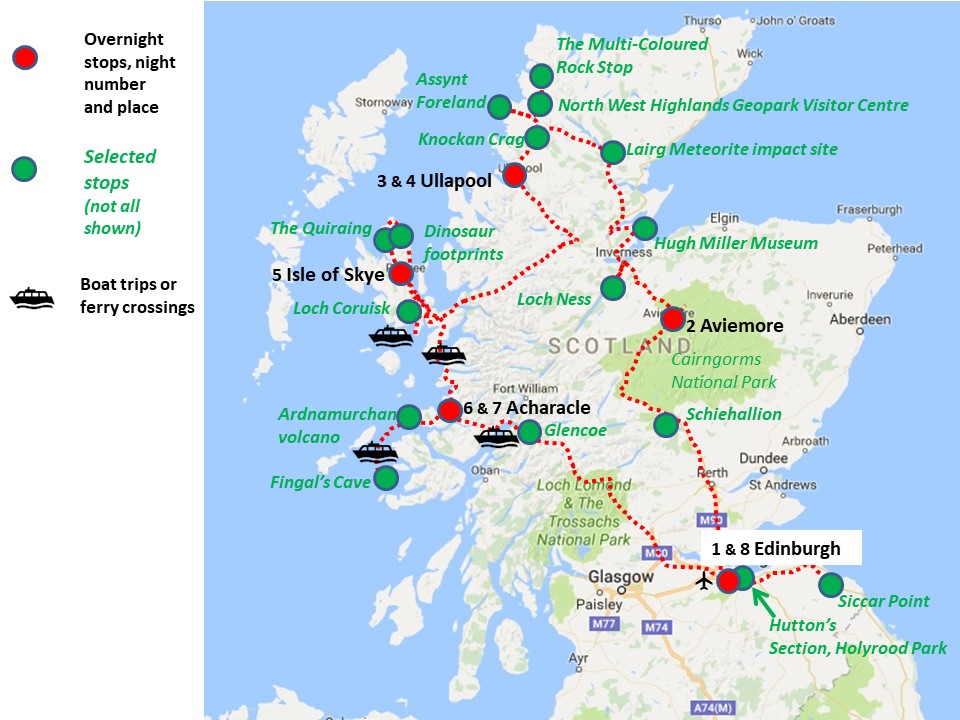

Above left: Abby at an information board describing the site where Hugh Miller founds some of his famous fish fossils on Cromarty beach.

Above middle: A mid-Devonian fish discovered by and named after Hugh Miller, in the the Hugh Miller Museum in Cromarty.

Above right: Some of the GeoWorld Travel group read the interpretations boards at the Ferrycroft Visitor Centre. The centre lies above a suspected. 1.2-billion-year-old meteor crater. Tektites from this impact are seen the following day.

Above left: Our group at the Moine Thrust at Knockan Crag in the North West Highlands UNESCO Geopark. This was the world’s first identified thrust fault. Its discovery revolutionised our understanding of how mountains form and finally settled the famous Highland Controversy.

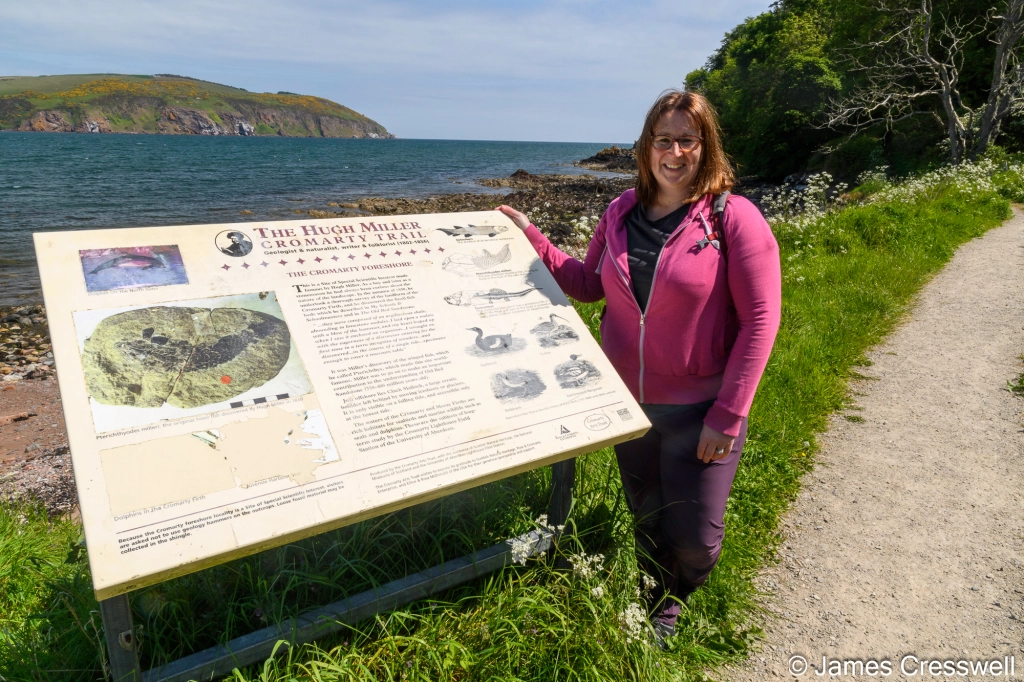

Above top right: The ‘Pipe Rock’ is Cambrian in aged and outcrops on the Hebridean Terrane below the Moine Thrust. The pipes are fossilised worm burrows.

Above bottom right: The famous ‘double unconformity’. Looking at the hillside beyond the loch, the top layer is made of Cambrian aged quartzite which sits unconformably on 1 billion-year-old Torridonian Sandstone which in term sits unconformably of 3-billion-year-old Lewisian Gneiss.

Above left: The ‘multi-coloured rock stop’ near Laxford Bridge. Here grey coloured three-billion-year-old gneiss is cut by 2.4 billion year old black coloured Scourie dykes, and both of these are cut by pink and white coloured 1.85 billion year old granitic dykes.

Above top right: Our group at the Glencoul Thrust. Here Cambrian aged sedimentary rocks are sandwiched between layers of three-billion-year-old gneiss. The Cambrian’s contact with the bottom layer of gneiss is an unconformity, while the contact with the top layer of gneiss is due to the older gneiss having being thrust over it via the Glencoul Thrust Fault.

Above bottom right: The ‘Graveyard Dyke’ is a 40m wide 2.4-billion-year-old Scourie dyke that cuts through 3.2-billion-year-old Lewisian Gneiss. Because the dyke is softer than the rock it intrudes it has been eroded more and forms a bay.

Above left: Anne points to an unconformity where one-billion-year-old Torridonian sandstone sits on three-billion-year-old gneiss.

Above middle: Abby and Barbara hold out a geological map of the Assynt Foreland with the icon peaks of Canisp, Suilven, Cul Mor and Stac Pollaidh visible in the background. The Assynt Forland has been voted as Britain and Ireland’s number one geosite. The mountain peaks are made of one-billion-year-old Torridonian Sandstone, and they sit on a one-billion-year-old palaeo-surface that is made from three-billion-year-old Lewsian gneiss.

Above right: The majestic mountain of Suilven is made of 1 billion yar old Torridonian Sandstone and sits unconformably on a basement of 3-billion-year-old Lewisian Gneiss.

Above left: The Clachtoll boulder is the world’s oldest known boulder. It is made of three-billion-year-old Lewisian Gneiss and fell down a cliff and landed in mud one billion years ago.

Above top right: Sharon points to one-billion-year-old mudstone that was injected into to the three-billion-year-old gneiss, which makes up the Clachtoll boulder, when it crashed to earth.

Above bottom right: The GeoWorld Travel scale card sits on 1.2-billion-year-old mudstone of the Stoer Group that contains green glassy fragments. These are interpreted as a tektites that fell to earth after a nearby meteor impact.

Above left: Anne points to a dinosaur trackway at Brother’s Point (Rubha nam Brathairean), Isle of Skye.

Above top right: Local palaeontologist Dugie Ross points out dinosaur tracks at Brother’s Point.

Above bottom right: A sauropod dinosaur track at Brother’s Point.

Above left: The Quirang on the Isle of Skye – this is the largest mass movement landslip in Britain. Paleogene lavas have slipped on the softer Jurassic aged sedimentary rocks that lie beneath.

Above right: The Old Man of Storr, like the Quirang, is part the largest mass movement landslip in Britain.

Above top left: A cliff of Jurassic aged sandstone at Elgol, Isle of Skye. The cliff is cut by a Paleogene aged dyke and has honey-combed weathering on its lower surface.

Above top right: Common seals seen on the boat tour to Loch Coruisk, Isle of Skye.

Above bottom left: A glacial erratic of gabbro resting on gabbro at Loch Coruisk in the Black Cuillin Mountains, Isle of Skye. These rocks were formed as the magma chamber of the 50-million-year-old Skye volcano.

Above bottom right: Our group returns to our boat, the ‘Misty Isle’, in the Black Cuillin. The rocks in the background are made of peridotite and formed by fractional crystallisation of the Skye volcano magma chamber.

Above top left: Caitlin and Anna inside Fingal’s Cave on the Isle of Staffa. The columns formed as magma from the Isle of Mull volcano was able to slowly cool.

Above top right: James and Abby in front of Fingal’s Cave.

Above bottom left: Basalt columnar cooling joints on Staffa.

Above bottom right: Fingal’s Cave and the Boat Cave on the Isle of Staffa. The island can be seen to consist of three layers: a top lava layer that cooled relatively quickly preventing perfect columns forming, below this is a layer of perfect basalt cooling columns that possibly represent a sill rather than a lava layer. The bottom layer is a layer of consolidated volcanic ash.

Above top left: A puffin on the island of Lunga

Above top right: The Harp Rock on Lunga is a breeding colony of thousands of guillemots and kittiwakes.

Above bottom left: A rare sighting of Risso’s Dolphins on our return from Staffa and Lunga.

Above bottom right: Common Dolphins seen on our return from Staffa and Lunga.

Above left: Some of our group right in the centre of the former Ardnamurchan volcano.

Above right: Slate cut by a vogesite dyke in the Ballachulish slate mine.

Above left: The GeoWorld Travel group at Glencoe. The glacially eroded rock of Glencoe originally formed in a Devonian super volcano.

Above top right: The ‘Three Sisters’ in Glencoe. The mountains are made of Devonian ignimbrite from pyroclastic flows and layers of rhyolite.

Above bottom right: Holyrood Park in the City of Edinburgh. In the background, the castle can be seen sitting on a Carboniferous aged volcanic plug. In the foreground Salisbury Crags, the world’s first identified Sill can be seen, with the famous Hutton’s Section just behind the fencing.

We run this geological tour of Scotland every year (sometimes twice a year!) and if you would like to join us, you can find all the details here: https://www.geoworldtravel.com/Scotland.php This is one of our most popular trips, so if you would like to join us, be sure to register your interest early!